Brief history

When Plutarch wrote about the life of Alexander the Great, he wasn’t present physically during the events to observe everything. Instead, he had to find reliable sources to write down Alexander’s biography.

In the same way, when Christians of the 2nd generation (the 60s-90s C.E.) wrote the Gospels (bios of Jesus) to preserve the memories of the Apostles, not necessarily as eyewitnesses, they had to gather many sources of information to write about what Jesus said and did. Within the Gospels, many sources are detectable. They could take the form of oral or written records, preserved in the Christian communities.

The sources behind these four accounts, are made of separate pieces, called units (stories, logia, anecdotes, and speeches), combined to form a narrative1. The stories aren’t completely linear: many chunks of material can be detach as individual pieces (e.g., a radical change of style or vocabulary), as if the authors copy / pasted earlier oral traditions2 and eyewitness testimonies3 from the Christian communities into their Gospels.

The question is, what are those sources which pre-date the Gospels?

Primary sources

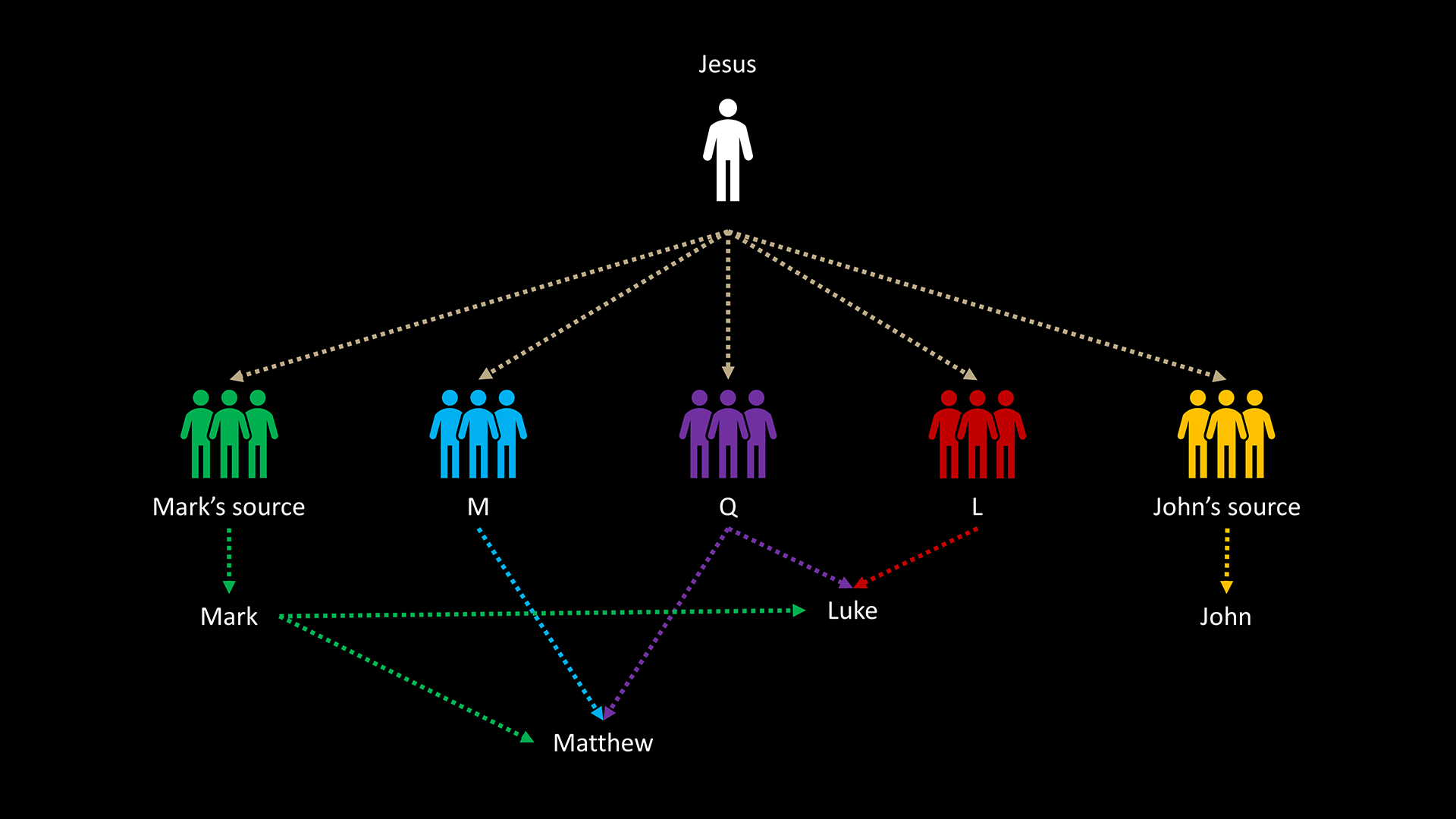

The 2-source hypothesis is the most popular theory among scholars: Mark wrote first, Matthew & Luke built on Mark’s Gospel combined with two other sources (M, L, Q), and John writes independently. This is a brief overview of the large units:

Secondary sources

Smaller units can also be detected10: creeds, hymns, Aramaic passages, passion narrative, sign source, saying source, speeches, discourse, etc.

Aramaic words

The original New Testament were composed in Koine Greek. A bit of words in Aramaic or Hebrew can been found scattered in the texts.

He took the child by the hand and said to her, “Talitha koum,” which means, “Little girl, I say to you, arise!“

Mark 5:41

…“Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Matthew 27:46

…“We have found the Messiah” (which is translated Anointed)…

John 1:41-42

The question is: where do they come from? Why did we need a small translation on the side?

Early origins

Between the time of Jesus’ death (33 CE) and the writing of the Gospels (66-96 CE), the oral transmission of his life & teachings went into three stages (Acts 1:8):

Acts 1-7

Jerusalem

33-35 CE

Acts 8-12

Judea & Samaria

35-48 CE

Acts 13-28

Gentile

48-66 CE

From Aramaic to Greek

Stories about Jesus were first circulated among Aramaic-speaking people11 from the Palestine area (most likely the Jerusalem community because diaspora Jews mostly spoke Greek).

In 50 CE, Christians translated these Semitic stories into Greek (common language across the Roman Empire), so more people could understand them in the Gentile world12.

During the process, many terms in Aramaic didn’t exist in Greek, or they were typically “too Jewish” to be understood by an outsider (ex: Messiah, Son of Man, Sabbath, rabounni, etc.), so it was kept in their original wording.

Detecting signs of Aramaism

Behind the layers of Greek, hide several passages colored with an Aramaic root:

If a verse is preserved in Aramaic, it is probably kept from the time of the Palestinian church. It wasn’t changed not evolve from the Greek-speaking audience (ca. 50s)17.

This biblical criterion is called “Semitism” (either of Aramaic or Hebrew origins).

Only with the Aramaic translations, we get this result: Jesus was the Messiah (Jn 1:41), a Rabbi (Jn 1:38, 20:16), one of his disciples is named Peter (Jn 1:42), performed miracles (Mk 5:41, 7:34), feel abandoned (Mk 15:34, Mt 27:46) in Calvary (Mk 15:22, Jn 19:17). Peter also raised a woman called Tabitha (Acts 9:36). One apostle was named Barnabas (Acts 4:36). Judas died in the land of Akeldama (Acts 1:19).

As atheist NT scholar Maurice Casey said: Mark’s Gospel is partly dependent on eyewitness accounts by Aramaic-speaking disciples18.

Matthew & Luke allegedly composed a first version in Hebrew, then translated back into Greek19.

Creeds & hymns

The first Christians didn’t have any written Gospels available yet, so they have to come up with small ‘formulas‘ or ‘kerygma‘ (brief summary of their belief) to evangelize others / proclaim their belief (creeds) or to use as chants for prayers20 (hymns)21 for the liturgies, inspired by the Jewish practices22. Even the pagans sang hymns to their gods (ex: Orphic hymns, Isis hymn of Cyme, Mithras liturgy)23.

“They (the Christians) were in the habit of meeting on a certain fixed day before it was light, when they sang in alternate verses a hymn to Christ, as to a god”24

Pliny the Younger

Why are they creeds?

- easily translated back into Aramaic (Semitism)

- sound like Hebrew poetry (highly stylized)27

- mostly Christology (death, resurrection & deity of Christ)28

- can be removed from its context and the rest of the text still make sense & flow perfectly29

- the style, vocabulary and ideas don’t reflect their author

Dating

- no Christological development can be seen in Paul’s letters37

(48 – 67 CE) - exist before Paul’s letters to be included

- parallel with Old Testament38

(created at a time where the Church was predominantly Jewish) - created for early liturgies39, baptisms, exorcisms40, times of persecutions41

(clarifying what they believe)42

Content

- Luke 24:34

- John 1:1-18

- Romans 1:3-4

- Romans 10:9-10

- 1 Corinthians 8:6

- 1 Corinthians 11:23

- 1 Corinthians 15:3-8

- Galatians 1:23

- Philippians 2:6-11

- Colossians 1:15-20

- Colossians 2:9-15

- 1 Timothy 2:5-6

- 1 Timothy 3:16

- 2 Timothy 2:8

- 1 Peter 3:18-22

- 1 John 4:2

1 Corinthians 15:3-8

The most popular & earliest of all, is 1 Corinthians 15:3-557. It was formulated within few months58 to 3 years after the crucifixion59. Paul received that tradition either during his visit to Jerusalem in 36 CE60 or earlier in Damascus61. Gerd Lüdemann (atheist) puts the original formulation of this creed in Jerusalem62.

Why a few months? Because Christians who took refuge in Damascus originally came from Jerusalem (Acts 8:1). Before they leave the city, they would already hear the kerygma (Acts 2:22-33).

Paul probably added verses 6 to 863, after meeting with Peter and James three years later (Gal 1:18-19).

Since it parallels with the speeches in Acts (13:28-31) and the ending of Mark (15:37-16:7)64, it is more likely to be passed on or influenced by Peter himself.

Here’s why it’s early:

- two words ‘received’ & ‘delivered’ is a rabbinic term of passing a tradition65

(Paul got it from somewhere else) - contain parallelism: four lines of the word ‘that…’

(typically used for stylized texts like poems or songs, easy to memorize: suitable for catechism & proclamation of the faith) - ‘Christ’ is typically used for a Jewish audience

(‘Lord’ is used for Gentiles66) - Christ dying for our sins refers to Isaiah 53:5

“He was piercedfor our sins, crushed for our iniquity…”

- the third day refers to Hosea 6:2

“He will revive us after two days;on the third dayhe will raise us up to live in his presence.”

- ‘Cephas’ is Peter’s name in Aramaic

(can be easily identified for Jews) - presence of terms Paul typically don’t use67

Speeches in Acts

Nearly one-third of Acts is composed of speeches (295 out of 1000 verses)73.

While Luke recorded the story of Acts, the sermons of Peter (chapter 1-10) and Paul (chapter 14-28) in the narrative are derived from earlier traditions74 (they are separated units). It’s ‘possibly’ from Peter and Paul (similarity of language).

| Acts | 1 Peter |

| by the set purpose and foreknowledge of God (2:23) | according to the foreknowledge of God (1:2) |

| silver or gold I do not have (3:6) | such as silver or gold that you were redeemed (1:18) |

| the faith that comes through him (3:16) | you believe in God through him (1:21) |

| repent, therefore, and be converted (3:19-21) | must turn from evil and do good (3:11-12) |

| God shows no partiality (10:34) | Father who judges impartially (1:17) |

| as judge of the living and the dead (10:42) | to judge the living and the dead (4:5) |

Same thing with Paul‘s speeches in Acts 14 to 20 (don’t reflect the style of Luke78).

| Acts | Paul’s letters |

| serving the Lord with all humility (20:19) | serving the Lord (Rom 12:11) with all humility (Eph 4:2) |

| that I may finish the race (20:24) | I have finished the race (2 Tim 4:7) |

| complete the task I received from the Lord (20:24) | complete the task you received in the Lord (Col 4:17) |

Dating

The early speeches in Acts (1-15) can be dated around 33 to 48 CE79 for different reasons:

Content

Saying source “Q”

“Q” is a hypothetical source (shared content between Matthew & Luke, not found in Mark), focus on the “saying” of Jesus, rather than a whole narrative112. It is estimated to contain around 220-235 verses113, with 4,500 words, where this source exist only by logical necessity114. Strangely, it doesn’t speak about the passion story of Jesus.

Dating

Because it doesn’t speak of the passion of Jesus in Jerusalem, we can assume that it was recorded orally in a rural Galilee115(Palestine116), between 35 to 50s CE117. Jesus’ temptation on the mountain could reflect the crisis of Caligula (40 CE) to transform the temple into a sanctuary of imperial cult118. Assuming the nature of the content, the authors are probably devoted Jews (converted to Christianity) speaking Aramaic119 from Judea120.

Pre-Markan passion narrative

How do we know it exists?

Joel Marcus and other scholars gives us a few arguments127:

- Mark 1-10 is disorganized128, while 11-16 is a smooth & linear story129

- no clear time frame in 1-10, but it’s clearer with the passion narrative (series of connected events)

- it doesn’t make sense as individual units, but it does as a continuous story

- because a crucified Messiah & Son of God was so scandalous130, Christians needed a detailed passion story to quickly answer the questions of how Jesus ended up that way131

- a common unit that John’s Gospel shared with the Synoptics (multiply attested)

- Paul’s strong emphasis on the passion events132133

- well constructed (quality takes time to develop)

Origin

Dating

Scholars dates the passion source extremely early due to the presence of anonymous names.

William Lane Craig date that source around 33-37 CE136:

Caiaphas isn’t named but is called by the “high priest”. When the passion source was composed, everybody knew who was the popular high priest who condemned Jesus was (take as granted). It wasn’t necessary to display his name. He was in office from 18-37 CE (Jn 18:13).

Gerd Theissen date it between 30 to 60 CE, possibility in 41–44 CE137.

The author(s) hide the names of people who could be denounced for their crime (like Peter who cut the ear of the servant) and get into trouble with the local Jewish authority who hold on to their power until 70 CE (destruction of the Temple). After 70 CE, the Sanhedrin lost its influence.

While Mark hide people’s names, John exposed the anonymous people in the 90s CE, because after 70 CE, some of them already died a long time ago (e.g., Peter in 64-67 CE).

| Mark | John |

| the woman who anointed Jesus (14:3-9) | Mary (12:1-8) |

| bystander who cut the servant’s ear (14:47) | Peter and Malchus (18:10) |

| bystanders who stays at the cross (15:35) | 3 Mary & John (19:25-26) |

Alexander and Rufus (Mk 15:21) were named because they did nothing wrong, and would be easily identifiable as witnesses in the Jerusalem Christian community. Matthew & Luke don’t name them (not necessary).

John Dominic Crossan estimates that it would take five to ten years for the church to find the Scriptures necessary to construct the Passion story, thus the story of Jesus’ last week wasn’t an early Christian invention140.

Content

Some key elements are included in the passion narrative (especially to build a case for the resurrection):

- miracles of Jesus141

- Jesus’ divinity

(Mk 14:61-64) - Jesus’ crucifixion

(Mk 15:24) - Jesus’ burial

(Mk 15:42-47) - Joseph of Arimathea

(Mk 15:43) - discovery of the empty tomb by women

(Mk 16:1-8)

Jesus before 50 CE

Before reaching the outside world, Christianity started with the conviction that Jesus was resurrected, that He preach the Kingdom of God and perform miracles to prove it, and was God incarnated in the person of Jesus of Nazareth.

Recommended books

- Oscar Cullmann – The Earliest Christian Confessions

- John S. Loppenborg – Q, the earliest Gospel

- Joachim Jeremias – The Eucharistic Words of Jesus

- C. H. Dodd – The Apostolic Preaching and Its Developments

- Michael R. Licona, “Why are there differences in the Gospels? What we can learn from ancient biography”, (Oxford University Press, 2017), 3

- 2 Thess 2:13, 2 Thess 2:15, 2 Tim 2:2

- 1 Pet 5:1, 2 Pet 1:16-17, Jn 21:24, 1 Jn 1:1, Jn 19:35, Acts 2:32, 3:15, 4:18-20, 5:30-32, 10:39-40, 1 Cor 15:5-8, Mk 16:1, Mt 28:1, Lk 24:10, 1:2, Acts 1:21-22, 2:32, 4:19-20, 10:39-40, Jn 20:1, Heb 2:3-4, Acts 1:21-22

- Papias, Anti-Marcionite Prologue, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Eusebius

- William Lane Craig, “The Empty Tomb of Jesus”, in Gospel Perspective II, ed. R.T. France and David Wenham (Sheffield, JSOT Press, 1981), 190-191

- Kim Paffenroth, “The Story of Jesus According to L” (Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 1997), 144

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the Secular City: a Defense of Christianity”, (Grand Rapids: Baker Book, 1987), 154

- D. Moody Smith, “Johannine Christianity: Essays on its settings, sources & theology”, (University of South California Press, 1989), 63

- Robert W. Funk, “The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus”, (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998), 16– 18

- Bart D. Ehrman, “How Jesus became God: the exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee”, (New York: HarperCollins, 2014), 216

- Bart D. Erhman, “Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth”, (New York: HarperOne, 2012), 90

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the secular city: a defense of Christianity”, (Baker Academic, 1987), 145

- Abba, Raca, Rabbouni, Eli Eli lema sabachthani, Hosanna, Maranatha, mammon, Bartholomew, Barabbas, Boanerges, Gethsemane, Golgotha, Jot, tittle, Korban, Sikera, Gethsemane, Gabbatha, Akeldama, Bethesda, Boanerges, Cephas, Thomas, Tabitha

- Bart D. Erhman, “Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth”, (New York: HarperOne, 2012), 88

- Bart D. Erhman, “Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth”, (New York: HarperOne, 2012), 88

- Mk 5:41, 7:34, 15:22, 15:34, Mt 27:46, Acts 1:19, 4:36, 9:36, Jn 1:38, 1:41, 1:42, 5:2, 9:7, 19:13, 19:17, 20:16

- Bart D. Erhman, “Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth”, (New York: HarperOne, 2012), 92

- Maurice Casey, “Jesus of Nazareth: An independent historian’s account of his life and teaching”, (Edinburgh: T and T Clark, 2010), 109

- Eusebius, “History of the Church”, 6.14

- Col 3:16, Eph 5:19, Acts 16:25, Heb 2:12, 1 Cor 14:15, 26, James 5:13

- Bart D. Ehrman, “How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee”, (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 215

- James D.G. Dunn, “Did The First Christians Worship Jesus? The New Testament Evidence”, (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 37

- Raymond E. Brown, “An introduction to the New Testament”, (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1997), 491

- Pliny The Younger, “Letter to Emperor Trajan”, 7-10

- Bart D. Ehrman, “How Jesus became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee” (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2014), 216

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the secular city: a defense of Christianity”, (Baker Academic, 1987), 148-149

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the Secular City: A Defense of Christianity”, (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1987), 147

- Oscar Cullmann, “The Earliest Christian Confessions” (translated by J.K.S. Reid, (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1949), 38

- Bart D. Ehrman, “How Jesus became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee” (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2014), 217

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the secular city: a defense of Christianity”, (Baker Academic, 1987), 148-149

- Gary R. Habermas, “The historical Jesus: ancient evidence for the life of Christ”, (College Press Publishing Company, 1996), 144-170

- Bart D. Ehrman, “Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth”, (HarperOne, 2012), 205

- Martin Hengel, “Between Jesus and Paul: Studies in the Earliest History of Christianity”, (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1983), 31

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the secular city: a defense of Christianity”, (Baker Academic, 1987), 148

- Bart D. Ehrman, “How Jesus became God: the exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee”, (New York: HarperCollins, 2014), 216

- Ralph P. Martin, “Carmen Christi Revisited”, in Where Christology Began: Essays on Philippians 2, eds. Ralph P. Martin and Brian J. Dodd (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1998), 2

- Martin Hengel, “Studies in Early Christology”, (Edinburgh: T and T Clark, 1998), 389

- James D.G. Dunn, “Did the first Christians worship Jesus? The New Testament evidence”, (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 103-111

- Oscar Cullmann, “The Earliest Christian Confessions” translated by J. K. S. Reid, (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1949), 22

- Justin Martyr, “Dialogue with Trypho”, 30:3; 76:6; 85:2

- Acts 4:3-22, 5:17-42, 6:8-8:1, 8:3, 9:2, 9:23-24, 12:1-5, 13:44-51, 14:5-6, 14:19-20, 16:16-24, 17:1-15, 18:12-17, 19:23-41, 19:27-3020:19, 23:12-14

- Ralph P. Martin, “Worship in the Early Church”, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974), 62

- Joachim Jeremias, “The Eucharistic Words of Jesus”, (London: SCM Press Ltd, 1966), 101-105

- Hans Conzelmann, “On the Analysis”, 18-20

- James D.G. Dunn, “Did The First Christians Worship Jesus? The New Testament Evidence”, (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 58

- Raymond E. Brown, “An introduction to the New Testament”, (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1997), 491

- Rom 1:3-4

- 1 Cor 15:3-8, Rom 1:3-4, Col 2:9-15, 1 Peter 3:18-22, Lk 24:34

- John 1:1-18, Col 1:15-20

- 1 Peter 3:18-22

- 1 Cor 11:23

- 1 Peter 3:18, 1 Cor 15:3-8, Phil 2:6-11, Col 1:15-20

- 1 Cor 15:3-8, Lk 24:34

- John 1:1-18, 1 Tim 3:16, 2 Tim 2:8, Phil 2:6-11, Col 1:15-20, 2:9-15, 1 Jn 4:2

- Rom 1:3-4, 2 Tim 2:8

- 1 Tim 3:16, 1 Peter 3:18-22

- Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “First Corinthians”, (Yale University Press, 2008), 543

- James D.G. Dunn, “Christianity in the making (vol 1): Jesus Remembered”, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 855

- Gerd Lüdemann, “The Resurrection of Jesus”, translated by Bowden (Fortress, 1994), 171-172

- Gal 1:18, Gary R. Habermas, “The Historical Jesus: Ancient Evidence For The Life Of Christ”, (Joplin, MO: College Press Publishing, 1996), 155

- Acts 9:3-18, Jean Héring, “The First Epistle of Saint Paul to the Corinthians (tr. A. W. Heathcote and P.J. Alcock; London: Epworth, 1962), 158

- Gerd Lüdemann, “The Resurrection of Jesus”, translated by Bowden (Fortress, 1994), 36

- Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “First Corinthians”, (Yale University Press, 2008), 542

- William Lane Craig, “On Guard: Defending Your Faith with Reason and Precision”, (David C Cook, 2010), 222

- Josephus, “Antiquities of the Jews”, 13.297

- Acts 16:31; 20:21, 24, 35; 21:13, 22:10, 18-19; 26:15

- Joachim Jeremias, “The Eucharistic Words of Jesus”, (London: SCM Press, 1966), 101-102

- 1 Cor 15:4, Jn 2:1

- Mt 28:1, Mk 16:2, Lk 24:1, Jn 20:1, Acts 20, 1 Cor 16:2, Rev 1:10

- 1 Cor 15:3

- Rom 1:17; 2:24; 3:4,9,10; 4:16,17, 8:36; 9:12,13,32,33; 10:15; 11:7,8,26; 15:3,9,21, 1 Cor 1:31; 2:9; 3:19; 6:16; 10:7; 15:45; 2 Cor 4:13; 8:15; 9:9

- Gal 1:17-19

- Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “The Acts of the Apostles: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary”, (Yale University Press, 1998), 103

- Bart D. Ehrman, “Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth”, (New York: HarperOne, 2012), 109

- Acts 10:36-43

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the secular city: a defense of Christianity”, (Baker Academic, 1987), 155

- C. H. Dodd, “The Apostolic Preaching And Its Developments”, (Willett Clark and Company, 1937), 24

- G.N. Stanton, “Jesus of Nazareth in New Testament Preaching”, (Cambridge University Press, 1974), 111

- C. H. Dodd, “The Apostolic Preaching And Its Developements”, (Willett Clark and Company, 1937), 22-24

- John Drane, “Introducing the New Testament (Fourth Edition)”, (Oxford: Lion Hudson Limited, 2019), 225

- R. A. Martin, “Syntactical Evidence of Aramaic Sources in Acts I-XV”, NTS 11/1 (1964), 38-54

- C. H. Dodd, “The Apostolic Preaching And Its Developments”, (Willett Clark and Company, 1937), 22-24

- Acts 16:10-17, 20:5-15, 21:1-18, 27:1-28:16

- Bart D. Ehrman, “Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth”, (New York: HarperOne, 2012), 109

- John Drane, “Introducing the New Testament (Fourth Edition)”, (Oxford: Lion Hudson Limited, 2019), 225

- G.N. Stanton, “Jesus of Nazareth in New Testament Preaching”, (Cambridge University Press, 1974), 111

- William Lane Craig, “The Son Rises: Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus”, (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1981), 49

- Gary R. Habermas and Michael R. Licona, “The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus”, (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2004), 261

- Acts 9:22; 17:3; 18:5; 18:28;

- Acts 16:31; 20:21, 24, 35; 21:13, 22:10, 18-19; 26:15

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the secular city: a defense of Christianity”, (Baker Academic, 1987), 155

- Ralph P. Martin, “Worship in the Early Church”, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974), 59

- Acts 19:5, 13, 17; 28:31

- Ralph P. Martin, “Worship in the Early Church”, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974), 60

- Rom 10:9, 2 Cor 4:5, 1 Cor 12:3

- Acts 2:22, 3:6, 4:10, 6:14, 10:38

- Acts 13:23

- Acts 2:22, 4:10, 5:38

- Acts 10:37, 13:24-25

- Acts 2:22, 10:38

- Acts 2:25-31, 3:21-25, 4:11, 10:43, 13:27-37

- Acts 2:27, 2:36-38, 3:14, 3:18-20, 4:10, 5:31, 10:36, 13:23, 13:33-35

- Acts 3:13, 13:28

- Acts 3:13-15, 13:27-29

- Acts 13:29

- Acts 2:24, 31-32; 3:15, 26; 4:10; 5:30; 10:40; 13:30-37

- Acts 10:40-41, 13:31

- Acts 2:32; 3:15; 5:32; 10:39; 41; 13:31

- Acts 2:38-39; 3:19-23; 4:11-12; 5:32; 10:42-43; 13:26, 38-41

- Acts 2:22-24, 36; 3:13-15; 10:42; 13:32-33

- Acts 2:33, 3:21, 5:31

- John S. Kloppenborg, “Q the earliest Gospel: an introduction to the original stories and sayings of Jesus”, (Louisville, London: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 65

- Raymon E. Brown, “Introduction to the New Testament”, (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1997), 117

- John S. Kloppenborg, “Q the earliest Gospel: an introduction to the original stories and sayings of Jesus”, (Louisville, London: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 2

- John S. Kloppenborg, “Q the earliest Gospel: an introduction to the original stories and sayings of Jesus”, (Louisville, London: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 62

- Gerd Theissen, “The Gospels in Context: Social and Political History in the Synoptic Tradition”, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991), 25

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the Secular City: a Defense of Christianity”, (Grand Rapids: Baker Book, 1987), 154

- Gerd Theissen, “The New Testament”, (London: T&T Clark, 2003), 37

- John Drane, “Introducing the New Testament (Fourth Edition)”, (Oxford: Lion Hudson Limited, 2019), 314

- John S. Kloppenborg, “Q the earliest Gospel: an introduction to the original stories and sayings of Jesus”, (Louisville, London: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 65-68

- Mt 8:5-13/Lk 7:1-10, Mt 11:2-6/Lk 7:18-23, Mt 9:32-34/Lk 11:14-23, Mt 12:43-45/Lk 11:24-26

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the Secular City: a Defense of Christianity”, (Grand Rapids: Baker Book, 1987), 154

- Joel Marcus, “Mark 8-16”, (Yale University Press, 2009), 925

- Richard Bauckham, “Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony”, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006), 183

- William Lane Craig, “On Guard: Defending Your Faith with Reason and Precision”, (David C Cook, 2010), 225

- Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “The Gospel According To Luke X-XXIV”, (New York: Doubleday, 1985), 1361

- Joel Marcus, “Mark 8-16”, (Yale University Press, 2009), 925-926

- Martin Hengel, “The Four Gospels and the One Gospel of Jesus Christ”, (London: SCM Press, 2000), 79-83

- Joachim Jeremias, “The Eucharistic Words of Jesus”, (London: SCM Press, 1966), 90

- Mk 8:31-32, 1 Cor 1:23, 2 Cor 13:4, Origen (Against Celsus 2.35,44)

- Martin Hengel, “Acts and the History of Earliest Christianity”, (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985), 46

- Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “The Gospel According To Luke X-XXIV”, (New York: Doubleday, 1985), 1360

- Rom 4:25; 5:8-10; 6:3-4, 1 Cor 1:23; 2:8; 11:23-25; 11:26; 15:3, 2 Cor 13:4, Phil 2:8; 3:10, Gal 2:20; 3:1; 3:13, 1 Thess 2:14-15, 5:10

- Gerd Theissen, “The Gospels in Context: Social and Political History in the Synoptic Tradition”, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991), 188-189

- J.P. Moreland, “Scaling the Secular City: A Defense of Christianity”, (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1987), 163

- William Lane Craig, “The Empty Tomb of Jesus”, in Gospel Perspective II, ed. R.T. France and David Wenham (Sheffield, JSOT Press, 1981), 190-191

- Gerd Theissen, “The Gospels in Context: Social and Political History in the Synoptic Tradition”, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991), 184-198

- Justin Martyr, “Apology 2.2”

- Josephus, “Vita 420”

- https://www.reasonablefaith.org/writings/question-answer/old-testament-prophecies-of-jesus-resurrection

- John P. Meier, “A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume II: Mentor, Message, and Miracles”, (Yale University Press, 1994), 620